Two Perspectives on Food Innovation: SodaStream vs. Monster Beverage

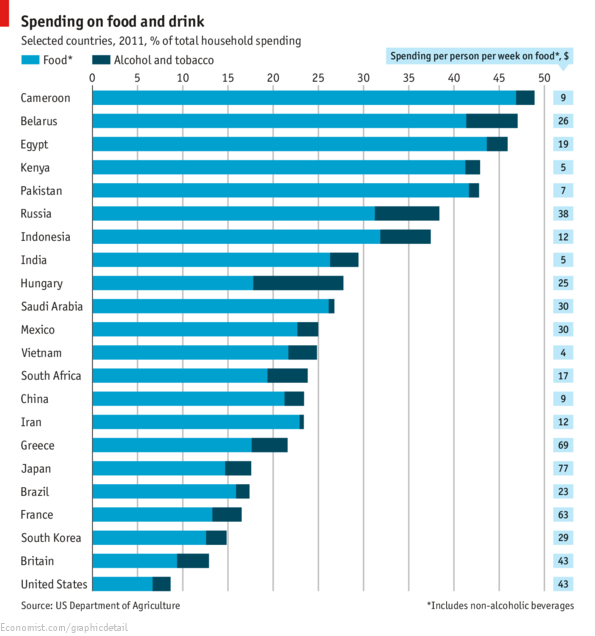

Food and beverage spending in the US is the lowest in the world as a percent of total household spending. Such a statistic could be considered an achievement if it weren’t for the (not-so-obvious to the naked eye) consequences. The US also spends the greatest percentage of GDP on healthcare in the industrialized world, yet has the worst health outcomes. Couple these facts with the fantastic leverage of digital media and you have a remarkable state of human nutrition today: for the first time in history more humans will die from over-consumption of food than from starvation. The responsibility for this outcome has a lot to do with the Western diet and how we define innovation in the food and beverage industry.

Two companies, SodaStream International Ltd and Monster Beverage Corporation, provide a stark perspective on the current state of food and beverage innovation (or lack thereof) and the challenges ahead from the consumer’s point of view. SodaStream ($1.4 billion market cap) manufactures an at-home device for making a variety of carbonated beverages including soft drinks of many flavors. Monster ($10 billion market cap) markets carbonated, sugary energy drinks under the Monster brand.

“Instead of blithely serving consumers’ nutritional and hydration needs, Monster’s products in fact are no different than some of housing’s most infamous derivative products that were, as the SEC described, designed to fail.”

The food and beverage industry’s track record of innovation has more to do with quantity than with quality. After all, how best to achieve the lowest food cost as a percentage of household spending than to trade quantity for quality? Too often, food is transformed into food products by replacing nutrients and fiber with salt, fat, sugar and preservatives – followed by ever more creative ways to distract children or excitable adults from the gimmick by shifting attention from the truth.

The truth is that food is not always what you think it is. Its physical transformation into a food product belies a much darker reality. Food undergoes the equivalent of a leveraged recapitalization designed to suit the financial goals of its creator. Consumption of junk food (for example a Twinkie or a sugary drink) is akin to a financial exchange where short-term gains are privatized and long-term costs are socialized in the form of horrific health outcomes. The metabolic donkeys – consumers – pay relatively little money and turn a blind eye to the health consequences of their food choices — instead hoisting the fantastic profits of companies like Monster and opting for a shortened, diseased life. By way of one small example, Apollo, a $16 billion private equity firm founded in 1990 by former Drexel Burnham Lambert banker Leon Black, recently purchased Twinkies (including Ho Hos and Ding Dongs) from bankrupt Hostess Brands for $410 million and will no doubt reap its financial rewards long before the health impacts materialize.

Think about it this way: your intangible net worth (health) gets hacked for profit when you consume unhealthy food products that are believed to be safe and innovative. Such food products are simply another form of so called innovation and have more in common with housing derivatives’ “innovation” and consequent bad outcomes.

SodaStream and Monster each have roots in the beverage industry’s formative years. Early in the 20th century, Monster (then called Hansen) produced fresh, non-pasteurized juices; SodaStream’s original soda machine was first invented in London in 1903. Today these companies represent extreme opposites in terms of operating strategy and philosophy, yet they share a common zeal as self-proclaimed innovators employing technology in the service of their customers.

For both companies, financial success is driven by brand appeal and rapid geographic expansion. Monster in particular sports a remarkable $1.7m revenue per full-time employee that places it among the top quartile of some of America’s highest-regarded tech companies – Apple’s revenue per employee is about $2m. In terms of growth and profit, they share similar high gross margins and cash flow with differences accounted for by their relative size and market channel.

For Monster, marketing and consumption are two sides of the same philosophical coin: on one level, the brand experience offers a fantastical connection to the world of extreme sports and being swept up in the romance of a revolutionary mob. On another level, the emotions around the brand offer temporary relief from the circular reasoning that renting your identity from a caffeinated, sugary drink company can only lead to more consumption after the stimulants wear off.

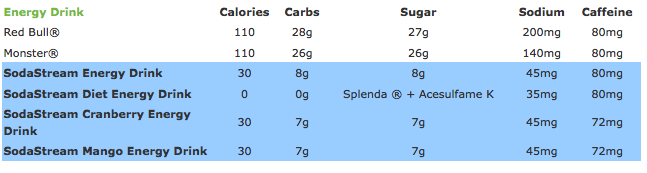

In contrast, Sodastream’s brand experience eschews the totem of blind consumption and instead is oriented to the merits of producing something (by hand) and reaping the rewards of conservation through the use of one’s ability to reason that a beverage can be as good or better with half the sugar, sodium, calories and cost.

The Monster Energy® drink logo is comprised of stylized claws of a monster that forms a large letter “M” – the company’s initials. The logo and brand concept is the work of McLean Design, a branding and packaging design firm. McLean Designs’ case study of Monster Beverage, “Creating a Monster,” is located here. Judging by the number of wrongful death lawsuits against Monster, the logo’s visual style appears to have roots to German Expressionist cinema – film noir – than to its supposed ethos of energy and vitality. The logo’s message seems to suggest that those insufficiently stimulated by television and video games can drink a $2 can of tech-noir and experience for themselves the fruits of food industry innovation.

Sodastream’s philosophy emphasizing the value of producing something to achieve conservation makes Monster’s operating strategy all the more unredeemable. The truth is that Monster produces nothing – literally. All of its beverage production is outsourced to third-party co-packers and suppliers. In fact, Monster even claims not to own the formulas used in the production of its beverages. According to company filings, Monster says, “we do not have possession of the list of flavor ingredients or flavor formulas used in the production of our products.” It’s core value appears to be a vast collection of trademarks (3,700 at last count) and an army of part-time marketing employees.

In Monster’s case, there is a clear social impact of a certain kind. Its customers measure in the tens of millions and its valuation in the billions. Since 2003, Monster’s stock gain of 20,318% makes Apple’s gain of 6,789% over the same period seem underwhelming. It’s not just that Monster’s sugary, caffeinated drinks are worse than any other product – it’s also about how they market and to whom. The company’s integrated brand and trade dress visuals offer convincing evidence that teenage males are the product’s targeted demographic.

Sugary drinks have been definatively inked to poor diet quality, weight gain, obesity, and, in adults, type 2 diabetes. Sugary drinks are a particular focus among leading health organizations seeking to reign in anti-social marketing practices. According to the Centers for Disease Control (CDC), males drink more sugar drinks than females – and teenagers and young adults consume more sugar drinks than any other age group. And according to a recent report by the American Heart Association (AMA), 180,000 obesity-related deaths worldwide are linked to sugary drinks, including about 25,000 adult Americans. A recent AMA press release dated June 18, 2013 also states, “The AMA today adopted policy supporting a ban of the marketing of high stimulant/caffeine drinks to adolescents under the age of 18.”

SodaStream’s incredible 2009-2012 revenue CAGR of 47% speaks to a powerful trend among consumers that is unlikely to diminish. It has far fewer customers than Monster, but its rapid growth suggests its social impact is different if not opposite Monster’s – SodaStream’s brand and market acceptance is derived largely from health and environmental features. In particular, problem solving is at core of the company’s brand and philosophy. According to a ticker displayed on the company’s website, use of its product has resulted in avoidance of 3.4 billion bottles to date. In terms of health, SodaStream’s typical user consumes a fraction of the sodium, sugar and calories compared to sugary drinks of all types. This messaging appears to be catching on with consumers around the world as illustrated in this recent Super Bowl commercial.

In distribution, SodaStream is pursuing a variety of initiatives that are a first in the beverage industry. Its newest concept is a 4-door refrigerator manufactured by Samsung that contains a built-into-the-door soda making apparatus powered by SodaStream. This new product expands on the at-home consumer soft drink (CSD) market, satisfying consumers’ on-demand needs.

In contrast to SodaStream, Monster is playing defense. Legal battles and campaign contributions appear to be occupying more of Monster’s energies. A recent City of San Francisco law suit against Monster Beverage Corp states that Monster “promotes excessive consumption of its drinks” with statements such as: “bigger is always better,” “chug it down,” “throw [it] back,” a “smooth flavor you can really pound down,” and “the biggest chugger friendly wide mouth we could make.” Furthermore, in describing Monster’s “targeted advertising” toward children and adolescents, the City’s attorney explicitly refers to Monster’s various social media pages, including Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, and a “Monster Army” social networking site. In predictable fashion, as public concern boils over, Monster appears to be ramping up campaign contributions as a means of fighting off efforts to selectively tax or regulate caffeinated sugary drinks. According to OpenSecrets.org, Monster spent $160,000 in total in 2012, and so far in 2013 it has spent $300,000.

One recent attempt at Monster’s version of innovation involved the rollout of a line extension called Monster Energy Extra Strength Nitrous Technology®. The marketing message is that the can is supposed to be injected with nitrous oxide, or laughing gas (which it is not). The only laughable part of this whole story is the truth. Monster is a company with a single product that contributes directly to bad outcomes; its message printed on the can, “Unleash the beast” sums up its anti-social impact on society.

Like some brand concepts that serve to distract consumers from the consequences of consumption, Monster Beverage Corporation hides behind innovation’s positive connotations to obscure the truth about its motives and its product’s negative health consequences. Instead of blithely serving consumers’ nutritional and hydration needs, Monster’s products in fact are no different than some of housing’s most infamous credit derivative products that were, as the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) described, designed to fail. (Matthew Martens, a lawyer for the SEC, told a jury that convicted Fabrice Tourre that the deal Goldman’s Sachs’ Tourre put together was “secretly designed to maximize the potential it would fail” to the benefit of the hedge fund, which made about $1 billion.) Despite the fantastic short-term profits available today, tomorrow’s social costs borne by consumers and society in general ends up being orders of magnitude larger.

According to a recent study by Ryan Masters, PhD, who conducted research as a Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Health & Society Scholar at Columbia University’s Mailman School of Public Health, death has placed a sure hand – it appears the US may experience a decline on overall life expectancy linked directly to obesity. Perhaps thinking about the true meaning of innovation in food and beverage and unmasking the impostors is a way to address the problem.

Update: SodaStream was purchased by PepsiCo in 2018 for $3.2 billion.

References:

SodaStream International Limited

Monster Beverage Corp

Centers for Disease Control

Columbia University

OpenSecrets.org

World Health Organization

The ideas presented in this post do not constitute a recommendation to buy or sell any security.

Investors are advised to conduct their own independent research into individual stocks before making a purchase decision. In addition, investors are advised that past stock performance is not indicative of future price action.

You should be aware of the risks involved in stock investing, and you use the material contained herein at your own risk. Neither SIMONSCHASE.CO nor any of its contributors are responsible for any errors or omissions which may have occurred. The analysis, ratings, and/or recommendations made on this site do not provide, imply, or otherwise constitute a guarantee of performance.

SIMONSCHASE.CO posts may contain financial reports and economic analysis that embody a unique view of trends and opportunities. Accuracy and completeness cannot be guaranteed. Investors should be aware of the risks involved in stock investments and the possibility of financial loss. It should not be assumed that future results will be profitable or will equal past performance, real, indicated or implied.

The material on this website are provided for information purpose only. SIMONSCHASE.CO does not accept liability for your use of the website. The website is provided on an “as is” and “as available” basis, without any representations, warranties or conditions of any kind.

I must say I prefer the sodastream model